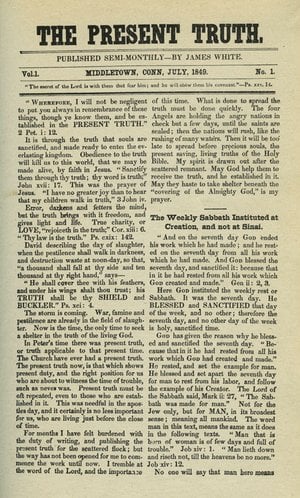

In July of 1849, James White packed copies of “The Present Truth” into a borrowed carpetbag and trekked eight miles to the post office in Middletown, Connecticut, United States. He was taking the first steps toward what would become a global publishing ministry.

Weeks before, the young, penniless Seventh-day Adventist Church pioneer had persuaded a local publisher to print 1,000 copies of the first issue of what is known today as “Adventist Review” magazine. White convinced the publisher that donations from Sabbatarian Adventists scattered across the U.S. Northeast would trickle in to cover the $64.50 printing costs. He was right.

“When God is behind something, what seems impossible is really only an opportunity for the Holy Spirit to work a miracle,” said Wilmar Hirle, current associate director for the world church’s Publishing Ministries.

That magazine grew into what Adventist historian George Knight called “probably the most effective instrument in both gathering and uniting the body of believers who would become the Seventh-day Adventists in the 1860s.”

In the 1840s, there were only a few hundred Sabbatarian Adventists, but that number grew to 3,500 by 1863 when the Seventh-day Adventist Church was officially established. Early church periodicals not only spurred evangelism, but they also provided a sense of spiritual community among early believers. Later on, publishing extended to lay ministry opportunities traditionally limited to pastors.

By 1844, when the Millerites wrongly expected the Second Coming of Christ, early believers had already distributed an “astonishing” 8 million pieces of literature, Hirle said. Boston, Massachusetts publisher Joshua Himes printed the Sabbath tracts and charts illustrating the prophecies of Daniel and Revelation that accompanied William Miller’s sermons in small churches throughout the U.S. Northeast.

But it wasn’t until 1848, after early church pioneer and prophet Ellen White was shown in vision that her husband, James, should launch a magazine that the Adventist publishing ministry began in earnest.

In the vision, White said God instructed James to “print a little paper and send it out to the people.” Despite the couple’s financial struggles, White said she had been assured that, with faith, the paper would eventually be “like streams of light that went clear round the world” (“Life Sketches”, pg. 125).

Early issues of “The Present Truth” were a platform for church leaders to clarify what had happened in 1844, discuss emerging doctrines such as the Three Angels Messages and, above all, unpack the Sabbath truth. Indeed, it was the seventh-day Sabbath that prompted the church to launch its first publishing house.

James and Ellen White, among other early church founders, grew increasingly concerned that a magazine proclaiming the Sabbath was being printed by a publisher who often worked on Saturday, Hirle said.

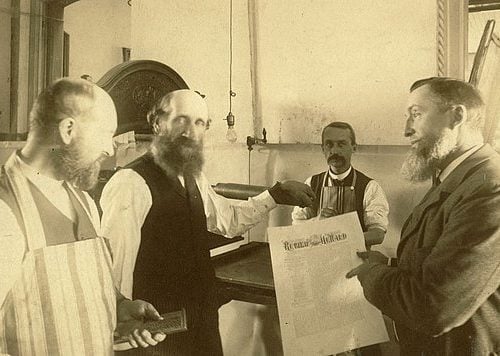

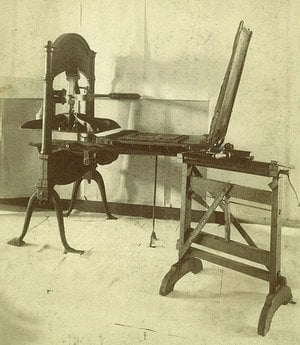

So, in 1853, early Adventists voted to establish a publishing house in New York. It was a house in the truest sense — early publishing leaders lived and worked together in a rented home in Rochester. Adventist pioneer Hiram Edson, who had recently sold his farm, lent the proceeds to purchase a Washington hand press. The machine took three days to produce one copy of what was then called “The Second Advent Review and Sabbath Herald.”

With no money to buy a paper cutter, Adventist pioneer Uriah Smith is said to have trimmed the edges of magazines with his penknife. Years later, Smith wrote, “We blistered our hands in the operation, and often the tracts in form were not half so true and square as the doctrines they taught.”

By 1855, the church’s publishing ministry had moved to Battle Creek, Michigan, and Smith, at age 23, was serving as editor, a role he would maintain in some capacity throughout his life.

As the church’s publishing ministry continued to grow in the mid-1800s, young Canadian immigrant George King developed the idea of subscription sale of Adventist publications. He was looking for a new ministry outlet after James White urged him to explore a career beyond the traditional role of pastor.

“James asked him to preach a sermon. It was a disaster,” said Hirle. “So he started literature evangelism.”

George King’s efforts to preach from house to house, rather than from the pulpit, in the U.S. and Canada helped grow Adventism into a global denomination. By the late 1870s, King was selling books and subscriptions to magazines such as “Signs of the Times.”

By 1903, the Adventist Church had reached 70 of the world’s countries. “In many of those places, [the church] established a presence because a literature evangelist was leading,” Hirle said.

Later, the church’s literature evangelism ministry would expand to include the first student literature evangelists in the early 1900s. Today, more than 20,000 Adventist students worldwide still spend their school breaks selling books to help cover tuition costs and share the Adventist message of hope.

Just as literature evangelism has grown, so has the church’s publishing ministry, which still remains at the “core” of Adventism, Hirle said.

Most recently, the Adventist Church embarked on a massive worldwide distribution of a modern adaptation of “The Great Controversy,” a book by Ellen White that highlights small groups of people who preserved an authentic form of Christianity throughout history. Church members worldwide distributed 100 million copies in 12 months.

Hirle said early church publisher James White, who, during thirty years of writing, printing and establishing publishing houses worldwide, often struggled to find support and overcome financial challenges, would likely be surprised to see how publishing is now widely supported in the church.

“If he could see publishing houses that print in a day what he was spending a year to print, I think he would be very happy,” he said.