I walked around the corner to the benches outside the lab, and sitting there was a thin but strong Arabic woman with a large gold ring in her nose. She was squeezing a stress ball as the blood flowed from her arm into a blood bag. I smiled at her, and she smiled back at me—not at all shyly. But when I, in my scrubs, sat down next to her, her smile was replaced by a look of slight shock.

She motioned to the needle in her arm and then pointed to me as if to ask, “Are you here to give blood too?”

I smiled, pointed to my arm, and then pointed to the blood bag while nodding my head. I couldn’t help laughing out loud when she started chattering away in Arabic with great excitement to her relative on the bench next to her. She then asked Anatole, the lab technician, if I was going to give blood for her sister. He assured her that I was indeed going to do that.

Her smile got even bigger as she looked at me with grateful eyes. I just smiled back, slightly amused by how incredulous she was that I, a nurse, would donate blood for her sister.

I watched her wince as Anatole pulled the large-bore, 14-gauge needle out of her arm, and I motioned and said in French, “That hurts!” She clicked her tongue and nodded in agreement.

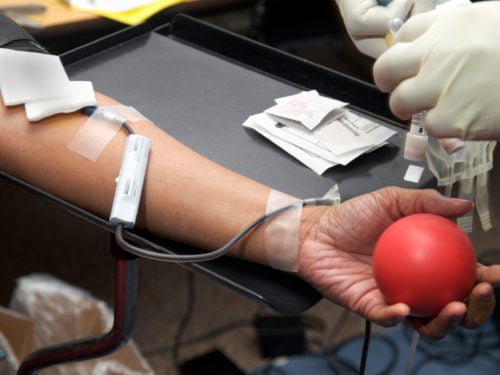

Then it was my turn. Anatole started prepping my arm and searching for a vein. I turned my head, because I can’t stand to watch the needle go in. The Arabic woman nodded her head as if to say, “You’re right not to want to watch,” and motioned for me to look away.

I turned my head back once to look at my arm because Anatole was asking me a question about which vein he should stick, and the Arabic woman quickly shook her head and motioned for me to turn my head away, saying that I shouldn’t look. To show respect for her concern, I turned my head away again. The woman put her hand up as a shield just to make sure that I wasn’t looking.

Anatole was successful in getting the needle into my vein. As I squeezed the stress ball to pump my blood into the blood bag, the rest of the family came over. The Arabic woman excitedly explained to them what was happening. I just smiled again; I was amazed at their excitement. They started talking among themselves, and Anatole explained to me that they were thanking me.

Anatole pulled the needle out of my arm when the blood bag was full, and the woman next to me cupped my face in her hands and said, “Merci, merci” (“thank you”). That may have been the only French word she knew.

I sat there for a little while so that I wouldn’t pass out from donating the blood. I just listened to the family and watched them.

At one point the Arabic woman’s relative next to her reached over and touched a little bit of my hair. I smiled and turned my head so that they could feel my hair. People in the African country of Chad are very intrigued by the hair of Nassara (“White people”) because it’s so different from their own.

There’s something truly amazing about giving blood in Africa, where you can meet the patient and family that it’s going to help. I have never before in my life enjoyed giving blood so much as in Chad. Unfortunately, the woman I was giving blood to was very sick. She had already had two bags of blood before her sister’s and mine. She had gotten appendicitis while pregnant.

A visiting American doctor, Dr. Johnson,* had performed an appendectomy on her, which is very dangerous during pregnancy. After surgery she just wasn’t recovering. She was still in a lot of pain and looked so exhausted.

Dr. Peter,* the missionary doctor, decided to give her some more blood and take her back into surgery to see if he could figure out what was wrong. That was the reason I was giving blood.

Later that night Ansley, one of the nurses I worked with came into the missionary house and said, “Guys, please pray for the little Arabic woman. She’s just not doing well.” Dr. Peter couldn’t find what was wrong and ended up removing the baby to try to give the woman a fighting chance at life. We stopped to pray in a group right then, and Ansley went back to work.

As she left I began praying silently to God; I was really upset at the thought that this woman might die. “God, please let her live. I gave my blood for her. Please don’t let it be for nothing.”

I stopped, astounded by the depth of what I had just prayed. How must Jesus feel? I can imagine Jesus praying the same prayer for me, pleading, “Father, please, I gave My blood for her. Please don’t let go of her.”

Then my thoughts carried me further: That’s how God feels about each of His children!

Each and every person that I come into contact with here on earth is someone Jesus gave His blood for—a gift that He doesn’t want to be in vain. Shouldn’t my prayers for their souls be just as earnest as my prayers for this Arabic woman’s life? Shouldn’t I be doing everything I can in my interactions with people to make sure that my Jesus didn’t give His blood for nothing?

All these thoughts opened my eyes to the value of the people that I am working with, as well as the value of every person in God’s sight.

I thought about how upset I would be if I had given my blood to this Arabic woman and it didn’t save her life. Then I realized that all I had experienced was a needle in my arm for a few minutes and the loss of some blood that I could easily spare. But Jesus, the Savior, had given His blood to the point of death. How much more precious a gift to be wasted, and how much more deeply He would feel the loss if it made no difference in the lives of people He dearly loves.

Since that moment of realization I always pray, “God, please help me to treat all people as worth the value You place on them. Help me to see with Your eyes.”

*Name changed.

This article originally appeared on Insight magazine on May 2012.