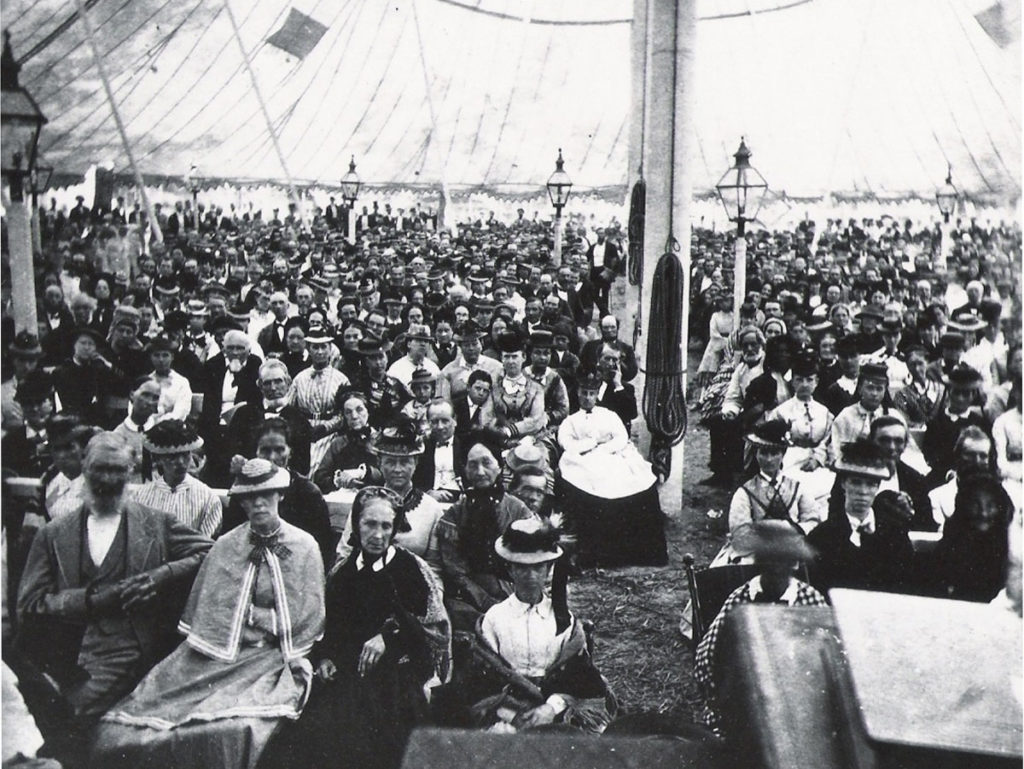

The early Adventist Church emerged from a climate of religious revival in the Northeastern United States. Camp meetings, such as this Millerite gathering, were a hallmark of the Second Great Awakening. [photos courtesy Office of Archives, Statistics and Research]

When Baptist preacher William Miller said Jesus was coming back on October 22, 1844, many Americans weren’t just surprised that he had set a date. The notion that Christ was literally returning was in itself a radical idea.

By the 19th Century, most established churches were preaching that the Second Coming was more myth than reality—and more human than divine. Religious leaders taught that a metaphorical “second coming” symbolized the rise of a new God-fearing, socially responsible generation.

But the Millerites’ belief in a literal Second Coming—along with new understandings of prophecy, the seventh-day Sabbath and the state of the dead—would prove pivotal. These core doctrines would anchor the early Advent movement amid a climate of religious turmoil.

The U.S. Northeast in the early 19th Century was a hotbed of revival. The so-called Second Great Awakening ignited movements such as the Shakers, early Mormons, the forerunners of the Jehovah’s Witnesses, the Millerites and a host of eccentric offshoots. In fact, upstate New York was dubbed the “burned-over district,” referring to the fact that evangelists had exhausted the region’s supply of unconverted people.

In this climate, the Millerites weathered the Great Disappointment, when the group expectantly, but futilely, waited for Christ’s return. With what Adventist historian George Knight calls the “mathematical certainty of their faith” dashed, many Millerites deserted the movement.

Those who remained were split over the significance of October 22. Some claimed the date was altogether bogus. Others maintained Christ had returned, but only in a spiritual, illusory sense. A final group—the future leaders of early Seventh-day Adventists—were convinced the date was right, but the event was wrong.

Reinvigorated by this possibility, they regrouped and returned to Scripture, determined to discover the truth. What they concluded is that instead of returning to Earth on October 22, Jesus had begun the last phase of his atoning ministry in the heavenly sanctuary.

A young Methodist woman named Ellen Harmon (later White) lent prophetic credibility to this interpretation. Her December 1844 vision of a “straight and narrow path” to heaven confirmed that prophecy had indeed been fulfilled on October 22 and galvanized what would be the denomination’s central focus on Christ.

Adventist historian David Trim is struck by the Millerites’ ability to transcend a “spectacularly wrong” initial message. While he says it’s true that apocalyptic movements often surprisingly keep some of their followers even when their ideas are “patently disproved,” these “aren’t the sort of people who go on to found a very successful church. That Adventists did so—it’s not proof that God is on your side, but it is proof that you have intelligent, rational leaders.”

Perhaps more telling is the Adventist Church’s belief that God was orchestrating events, Trim says. “I think early Adventists had a strong calling from the Holy Spirit. It’s terribly old-fashioned, but I believe our church was called into being at that time for a purpose,” he says.

They also demonstrated a keen desire for biblical truth, he says. “This is what sustains them when all of the other ex-Millerites are going down either eccentric routes or just very mainstream and cautious routes,” Trim says.

For early Advent believers, so-called “present truth” was dynamic. And indeed, as the few hundred Sabbatarian Adventists of the 1840s grew to 3,000 by 1863 when the Seventh-day Adventist Church was officially established, their doctrinal understanding underwent no less striking changes.

Early on, pioneers such as James White were fervent in their call to “come out of Babylon.” At first, this was a message to leave organized religion and return to gospel simplicity.

This doesn’t surprise religious historians, who have observed that every few generations, people feel compelled to go back to the fundamentals of their faith. Indeed, this trend fueled the Second Great Awakening.

But what is striking, Trim says, is the reversal White pulls as the movement expanded. By 1859, James had come to believe that the call to “come out of Babylon” actually meant to leave disorganization and accept church structure.

“This of course plays very nicely on the fact that Babylon ultimately comes from Babel—or confusion—and White says the call to come out of Babylon is actually to leave all this chaotic and incredibly exciting and fervent religious current and come into something a little more organized. So what it means to ‘come out of Babylon’ completely gets turned on its head and subverted,” Trim says.

But as they moved toward church structure, early Adventists didn’t lose their initial zeal. Rather, they were able to carve out a balance between the radicalism that pervaded much of the religious expression in the mid-1800s and the conservatism that would follow. It’s an equilibrium the Adventist Church still maintains today, Trim says, and it finds its roots in the longstanding tension between spirit and order, dating back to the early medieval church.

“You have to have the spirit because order becomes staid and ossified and hierarchical, but you have to have the order because the spirit becomes chaotic and self-destructive,” he says.

Adventist Church pioneer Ellen White was crucial in preserving this balance. Through her prophetic gift, Trim says White was ideally situated to temper inevitable squabbles between early Adventist leaders such as her husband, James, Joseph Bates, Uriah Smith, John Nevins Andrews, George Butler and others. All of them were “incredibly high-powered, driven individuals,” personalities necessary to propel a localized movement into a global church, he says.

While some students of church history might find tension between core leaders “disconcerting,” Trim says the early Advent movement is unique in that it stayed united in a climate where most religious groups tended to splinter off, following a charismatic leader, or dissolve altogether. Despite disagreement, Adventists ultimately rallied behind biblical truth achieved through prayer and Bible study or revealed through prophecy.

“These men are wholly persuaded that [Ellen White] is God’s messenger. If she says, ‘I have been shown this,’ they accept it even if they don’t initially like it,” Trim says.

“They’re very quick to debate, and they do so in very straight-up terms, but they’re also very quick to forgive and they don’t hold grudges,” Trim says. “They have an openness that would serve us well to copy.”

Modern Seventh-day Adventists might find early Adventist pioneers peculiar. Some didn’t believe in the Trinity or the personhood of the Holy Spirit, and thought Christ was a created being. Many observed Sabbath from 6 p.m. Friday to 6 p.m. Saturday, regardless of actual sunset times. They also had no qualms over eating unclean meats. All this, however, would change in the coming decades.

What today’s Adventists likely would recognize in their forbearers is conviction. In the Sabbath, Second Coming, Sanctuary and other fundamental beliefs, early Adventists believed they had discovered what Trim calls a “key” to unlocking the entirety of biblical truth.

“They realize that these doctrines are all saying the same thing about God, they’re all pointing in the same direction, and so early Adventists feel compelled to stand by them.

“This concern for truth is inspiring,” he says.

![Millerite Camp Meeting

The early Adventist Church emerged from a climate of religious revival in the Northeastern United States. Camp meetings, such as this Millerite gathering, were a hallmark of the Second Great Awakening. [photos courtesy Office of Archives, Statistics and Research]](https://www.adventist.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Early-Campmeeting-web-500x375.jpg)