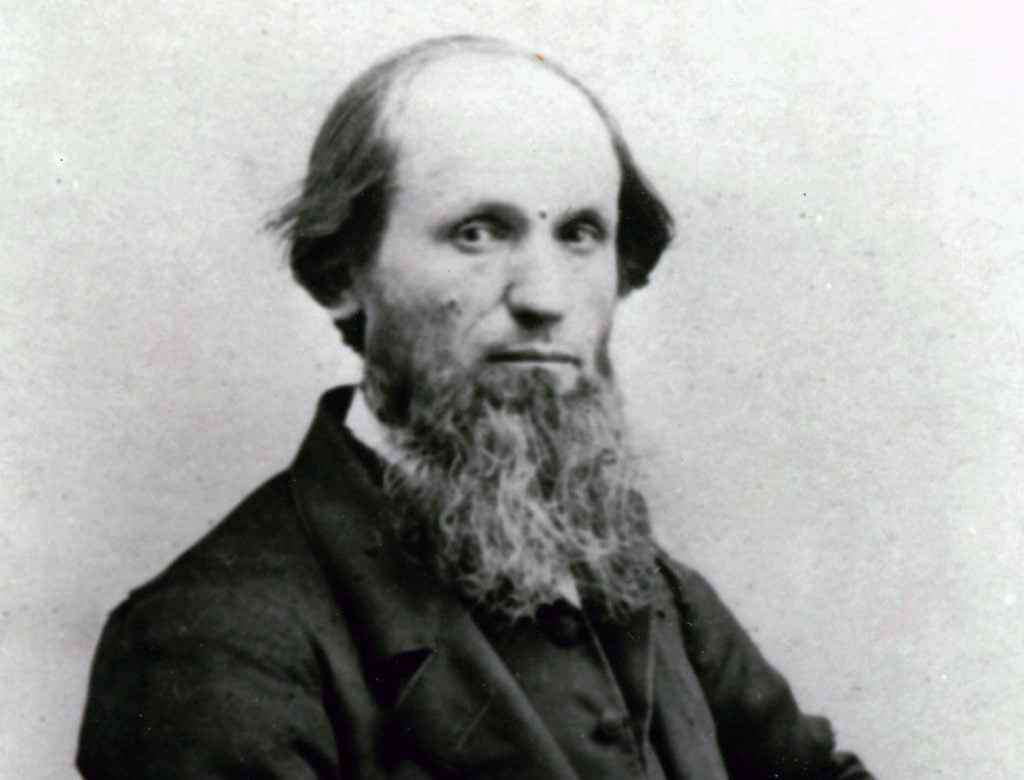

Though the Adventist Church didn’t endorse him, Michael Czechowski was the first person to take the Adventist message outside of the United States. He actually arrived in Switzerland a decade before John Nevins Andrews, who is widely known as the denomination’s first official missionary. [photos courtesy Office of Archives, Statistics and Research]

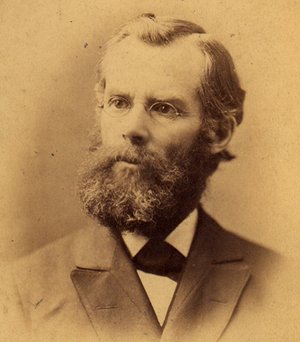

Though John Nevins Andrews is rightfully credited as the Seventh-day Adventist Church’s first foreign missionary, the preaching of the Adventist message in Europe actually preceded his 1874 arrival in Switzerland by a decade.

Michael Czechowski, a former Roman Catholic priest originally from Poland, had requested to be sent to his native continent to spread his newfound faith that heralded the soon Second Coming of Jesus. Adventist Church leaders, uncertain of his reliability and honesty, declined his request. He would, however, go on to become the fledgling denomination’s first overseas missionary, oddly enough, by validating their suspicions.

Czechowski, who had deserted his wife and children, later gained missionary sponsorship from the Advent Christian denomination – the main group of Sunday-keeping Adventists. Having his way paid, he ignored the teachings of his sponsors upon arrival in Europe in 1864 and proceeded to teach the Seventh-day Adventist message, gaining converts throughout the continent, including in Switzerland, Hungary, Italy and Romania.

With a church structure having recently been created, thus began the expansion of the Adventist message outside of the United States. But it would be many years before the Adventist Church would commit wholeheartedly to foreign mission.

Within the church at home – based in the U.S. state of Michigan – debate flared over the meaning of Jesus’ call in the Gospel of Mark to “Go into all the world.” Most of the 3,500-member church in 1863 thought reaching diverse immigrant populations within America was sufficient, some suggesting those immigrants would convert their friends and relatives in their mother country.

The 1871 General Conference Session passed a resolution to send “Bro[ther] Matteson as a missionary to the Danes and Norwegians”… in the nearby state of Wisconsin.

“It wasn’t our church’s finest hour,” says Adventist historian David Trim, who serves as director of the world church’s Office of Archives, Statistics and Research.

Meanwhile, in Europe, some of Czechowski’s followers accidentally discovered an Adventist magazine among his papers informing them that, to their surprise, they weren’t the world’s only Adventists. Adventists in the U.S., still arguing over the feasibility of taking their teachings beyond national borders, were similarly taken aback.

“Adventists in America were actually sort of embarrassed to learn that there were already Adventist believers in Europe,” Trim says.

The mutual discovery led to American Adventists inviting a Swiss representative to the 1869 General Conference Session. He arrived too late, but spent the next year in the U.S. learning Adventist beliefs more thoroughly before returning home as an ordained minister.

At that 1869 session, however, the establishment of a missionary society was a key step in triggering a two-decade process of reversing the church’s mindset toward mission. The transformation was aided by a boldness of the small group of believers who thought they in fact could reach the world, and more importantly, leadership was becoming increasingly comprised of former missionaries.

The church’s prophet and co-founder, Ellen White, later penned her strongest calls for oversees mission after spending time herself in Europe in the 1880s and Australia in the 1890s.

In 1901, she declared at the General Conference Session, “The vineyard includes the whole world, and every part of it is to be worked.”

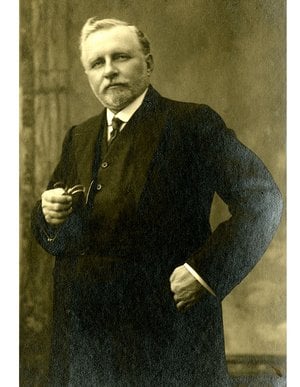

That same year, Arthur G. Daniells became the first missionary elected as the Adventist Church’s president, having served in New Zealand and Australia for 15 years.

“It’s a remarkable story of how our pioneers changed their mindset because they were such a small group,” Trim says. “The confidence of this tiny group to think they could reach the whole world is astonishing.”

The pattern for oversees mission can be traced back to when the church expanded to the west coast of the U.S. It was in 1868, one year before the landmark mission focus of the 1869 General Conference Session, that church leaders responded to a request for a minister in the far-off state of California. John N. Loughborough and D. T. Bordeau accepted the call and worked to build what would become a recipe for entering new areas – gain a sufficient following and then establish a printing press, a magazine and a medical facility.

The year 1874 was another key year for mission – widower Andrews, a former Adventist Church president, took his two children to Europe as the church’s first official missionary, and the denomination established its first mission periodical, “True Mission.” Also, Battle Creek College in Michigan was established to train ministers to work both in the U.S. and abroad.

By 1910 a steady stream of missionaries was heading out – the mission fields prior to the 1880s were joining the U.S. as the new Adventist homelands. The Germans took responsibility for Egypt, the Ottoman Empire and Russia, the Swedes for Ethiopia, the British for East and West Africa, and the Australians for Southeast Asia and the South Pacific. Jamaica, too, sent missionaries; one of them, C. E. F. Thompson, went to Ghana.

A new publication, “Mission Quarterly,” was established in 1912, telling the stories of missionary families, including the Stahls in South America, Gustav Perk in Russia, the Robinsons in South Africa, and others who had left the U.S. knowing they might never come back.

William A. Spicer, who was appointed church president following Daniells and had served as a missionary in India, published his thoughts on mission in the 1921 book, “Our story of Missions for Colleges and academies”: Mission “is not something in addition to the regular work of the church. The work of God is one work, the wide world over…. To carry the one message of salvation to all peoples … is the aim of every conference, every church, every believer.”